„AND YET IT MOVES” (1)

I admit that I'm indebted to readers interested in a profound metaphysical exposition regarding the spiritual basis of the visual arts, and even of all fields of art, that addresses the problem of consciousness and artistic vision. Such an approach, however, goes beyond the character of my structural concerns - focused on the pragmatics or application of theorized concepts. I will probably write it as a separate text in the future. Also, regarding the narrative appeal of the texts, I think it is not yet the right time to approach popularization. At this stage of conceptual initiation of the field of research - not as a normalized discipline - I think the technical message of the expositions is more important than the creative use of introduced notions.

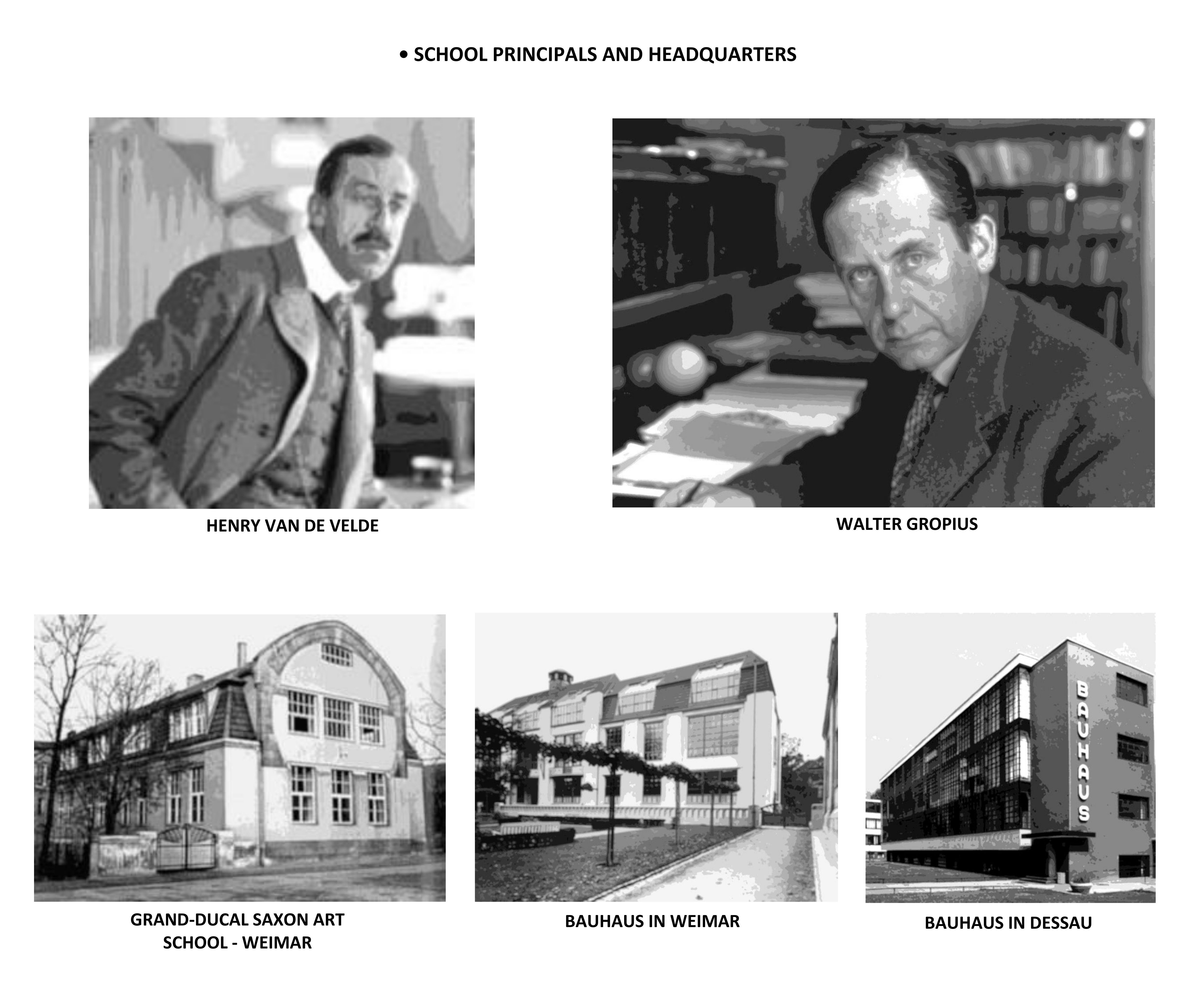

As I stated in EXPO 2 - META, the role that the artist or author should assume about the viewer is that of abnegation towards the semantic source of the work of arts's message (the signified), conveyed through the essentializing modeling of the structure (the signifier) and in the participatory horizon of facilitating the dialogue with the viewer (the meaning). Perhaps the artist who most openly and sincerely assumed this mission as a channel of transmission and herald of visual creation in the modern world was the German architect Walter Gropius.

As I stated in EXPO 2 - META, the role that the artist or author should assume about the viewer is that of abnegation towards the semantic source of the work of arts's message (the signified), conveyed through the essentialized modeling of the structure (the signifier) and in the participatory horizon of facilitation of the dialogue with the viewer (the meaning). Perhaps the artist who most openly and sincerely assumed this mission as a channel of transmission and herald of visual creation in the modern world was the German architect Walter Gropius.

In a letter dating from 1907 (the last year of his training as an architect) he confessed to his mother that he could not draw a single straight line. Due to a motor disease, the muscles and tendons of his hand were straining uncontrollably, cramping intensely, and causing him to break the tips of his pencils when drawing. The condition disappeared within five minutes of ceasing all effective activity (Isaacs R.R. 1991, p. 23). For this reason, Gropius assumed throughout his career a continuous teamwork and social effort to achieve his architectural-utilitarian goals with the utmost precision of essentialisation, with the help of and through collaboration with his working partners. Moreover, he has taken this socio-artistic communication skill to a higher level by materializing his most important project: Bauhaus. Gropius established the innovative School of Arts and Crafts through the transformation of the Grand-Ducal Saxon Art School from Weimar, to which leadership he was recommended after the end of First World War by Henry van de Velde, the school's previous director (MacCarthy F. 2019, p. 90-91).

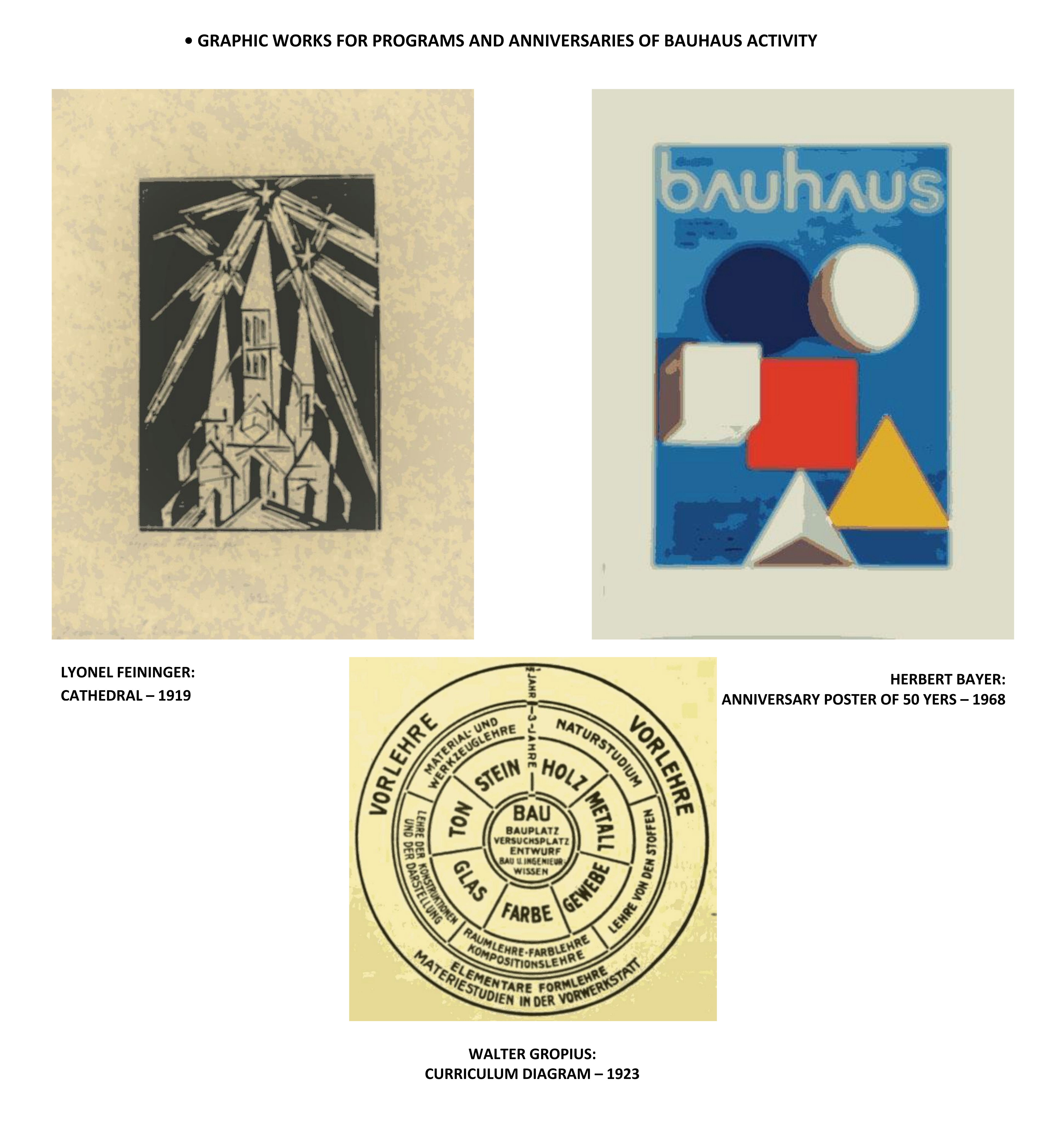

Instead of beauty and imitation of nature, Gropius preferred the functional and utilitarian artistic visual creation. Instead of academic emulation, Gropius followed a revival of creation activity in the spirit of the medieval guilds of stonemasons who built the Gothic cathedrals (Gropius W. 1923, p. 22-26, 31). For Gropius, the work of the medieval stonemasons was a model of cultural-artistic continuity from one generation to the next and of the syncretic and esoteric integration of all fields of art into a unified whole, seen symbolically as a CATHEDRAL:

«His high office must again find public recognition in the people's state; he must force it upon himself through that high humanity that stands above the work of the day, through an ardent interest in the everyday work. When the problems of painters and sculptors once again move his spirit [of the stonemason] as passionately as his own in the art of architecture, the works of these painters and sculptors must fill once again with an architectural spirit. He must once again gather like-minded artists around him in close, personal contact - like the masters of the Gothic cathedrals in the building lodges of the Middle Ages - and thus prepare the freedom cathedral of the future in new living and working communities of all artists, not hindered but supported by the people as a whole.» (Gropius W. 1919, p. 134-136)

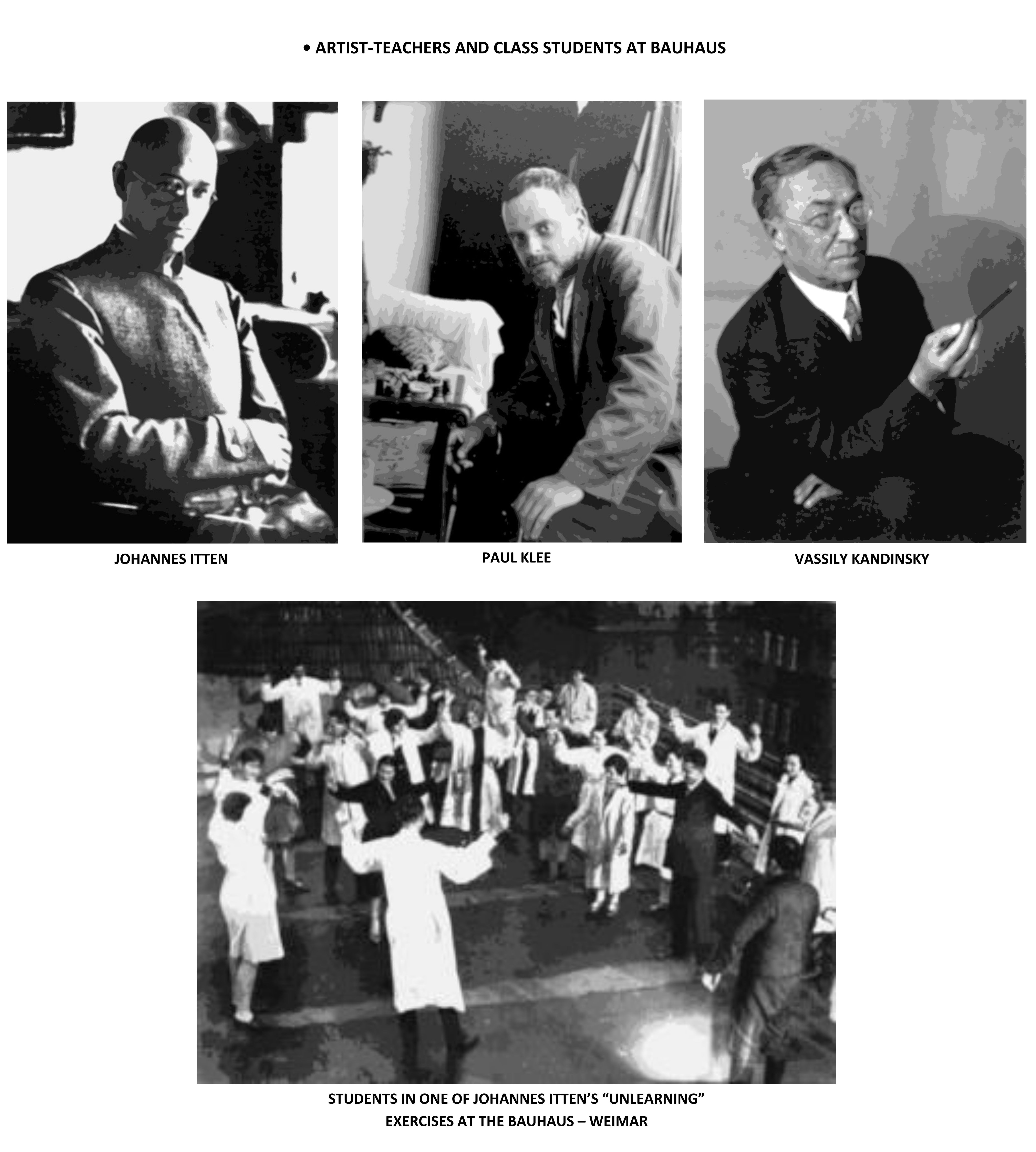

To achieve these goals, Gropius invited and welcomed to the Bauhaus, throughout the school's stages of development, artistic personalities with different esoteric, syncretic, and scientific ideologies but with a fundamental unified structural vision. I will mention here only Itten, Klee, and Kandinsky, whose theoretical conceptions initially guided me to the method of STRUCTURAL VISUAL ART RESEARCH (SVAR).

Johannes Itten was a follower of Mazdaism or Zoroastrianism. He organized the introductory course in the early years of the school's activity in Weimar. In this course, students controlled and came into contact with aspects of chromatic and tactile sensoriality and emotionality (Itten J. 1974, p. 25-32), which they combined lucratively with free, gestural body movement (Itten J. 1963, p. 7-18). Itten advocated syncretism between the visual arts and music by associating chromatic contrast of quantity with musical intervals expressed numerically by Pythagorean ratios of musical chord length (Itten J. 1974, p. 104-107). He also advocated an analysis of compositional space based on the gestural and rhythmic distribution of the contours of the surfaces evoked by the image of the work, reduced to essentialized directions, which formed geometric figures interpreted esoterically (Itten J. 1921). His principle of essentialisation was the counterpoint based on contrasts between related properties and applied to all structural-visual aspects (Itten J. 1930).

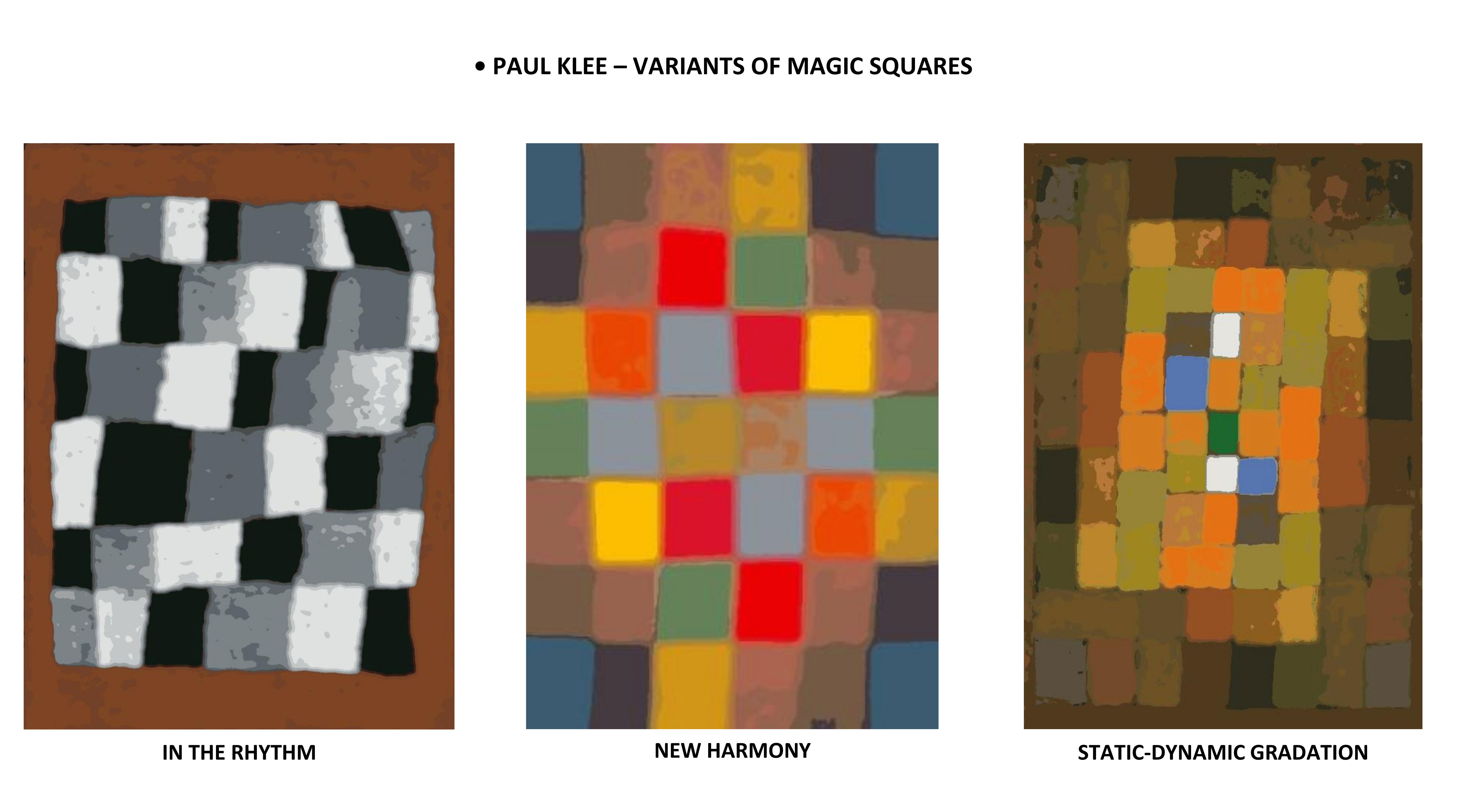

Paul Klee approached a multiple syncretic path by associating visual artistic structures with musical, literary-semiotic (Thurlemann F. 1982) and scientific-biological ones. Beginning in 1921, he taught technological workshop courses, including creative bookbinding, glass painting and weaving, mural painting, and "free painting" (Berggruen O. 2013, p. 94-96). His principle of essentialization was structural functionality (Klee P. 1961), inspired by the notion of mathematical function and equational balance. He conceived a composition by the induction of consciously constructed and modularly pre-conceived structures - as magic squares - which generated emergent attentional-perceptual and spatial effects through free and rhythmic permutational development, impossible to anticipate deductively at the constructive level. Thus, functionality makes a "bridge" between the two domains of composition: construction and its attentional-visual effect (Hasan Y. 1999, p. 159-163).

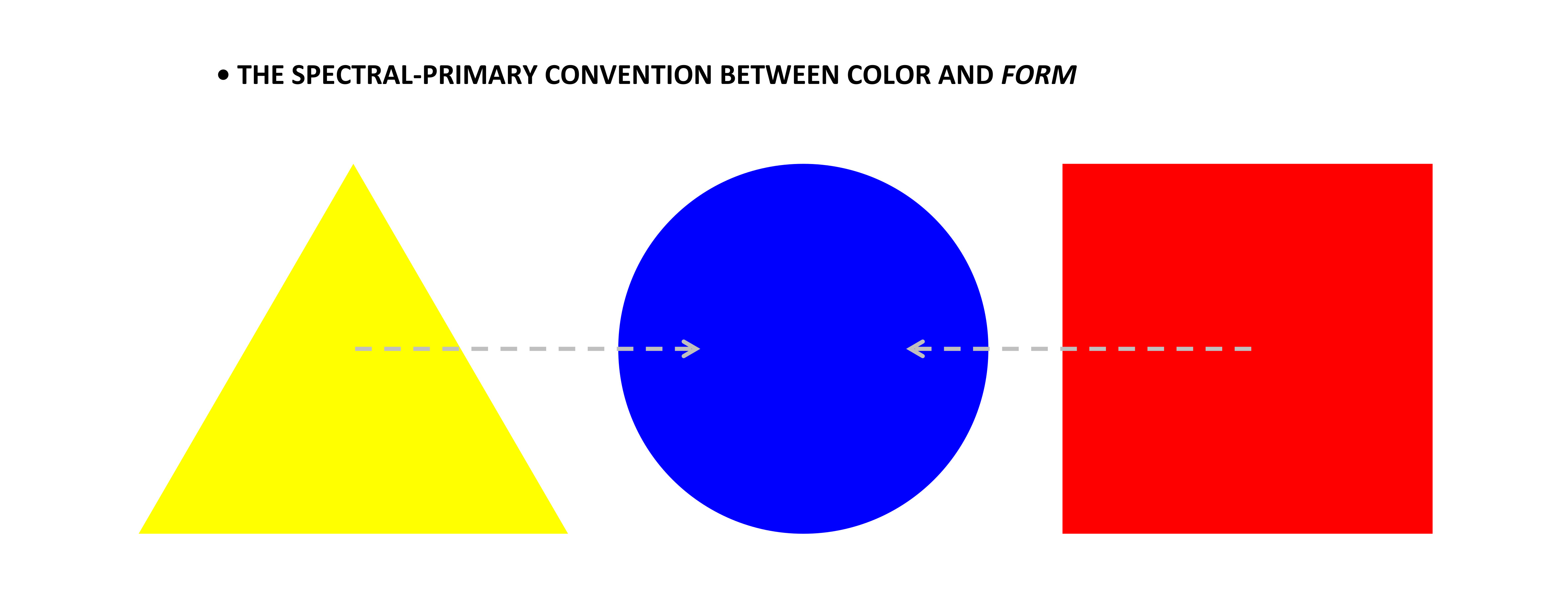

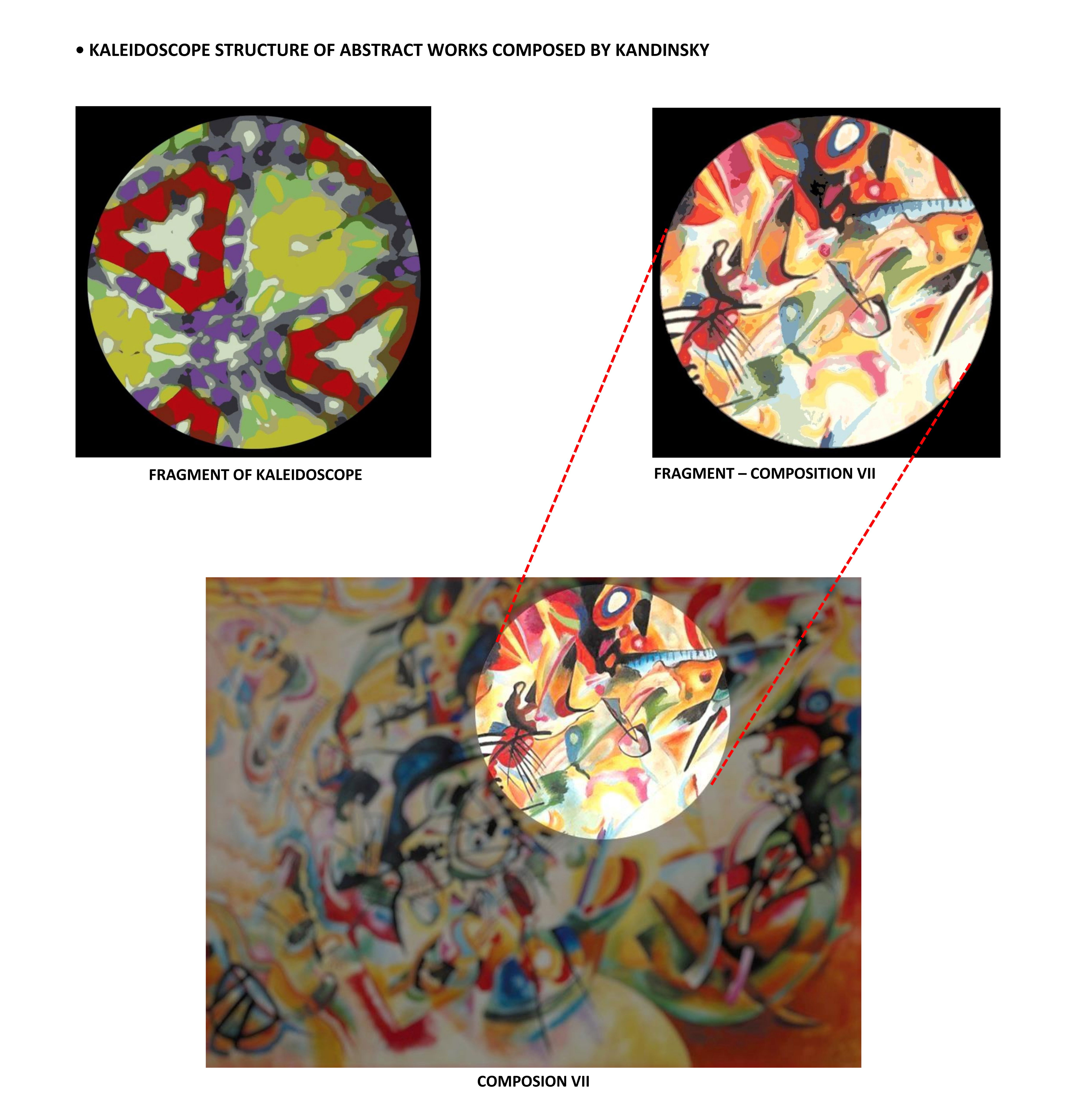

Vassily Kandinsky was a follower of anthroposophy. He advocated various syncretic directions of association between the visual arts and music, dance, and proto-scientific notions of Platonic inspiration. He proposed, based on the ancient theory of the elements of matter (air, water, earth, and fire), symbolic correspondence between basic geometric figures and primary tonal-chromatic contents (Plato 1965). Having the most extensive period of teaching activity at the Bauhaus of the artists mentioned above, Kandinsky succeeded in developing a structural theory that intended the synthesis of color and compositional dynamics. "On the Spiritual in Art," (Kandinsky V. 1921) and "Point and Line in the Plane" (Kandinsky V. 1926) are the two works in which Kandinsky exposed his structural theory of form and elements, which he intended as an introduction to a general science of art.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The purpose of the topological presentation in this expositional chapter is to apply a-chromatic or dynamic properties and their relationships to the context of the compositional structure of an established work of visual art. The presentation will contain two alternative parts: (1) form and elements in Kandinsky's theory and (2) their applied developments in the structural visual art research method. Although my discussion will be both comparative and critical (colored in blue) regarding Kandinsky's approach (bold-italic text notions), its aim is synthetic and, therefore, the same as the one mentioned by the artist in the introduction to ”Point and Line in the Plane":

«The investigation should proceed in a meticulously exact and pedantically precise manner. Step by step, this "tedious" road must be traversed—not the smallest alteration in the nature, in the characteristics, in the effects of the individual elements should escape the watchful eye. Only by means of a microscopic analysis can the science of art lead to a comprehensive synthesis, which will extend far beyond the confines of art into the realm of the "oneness" of the "human" and the "divine."» (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 21)

I, however, will refer to a much narrower horizon of synthesis - purely structural and visual-artistic.

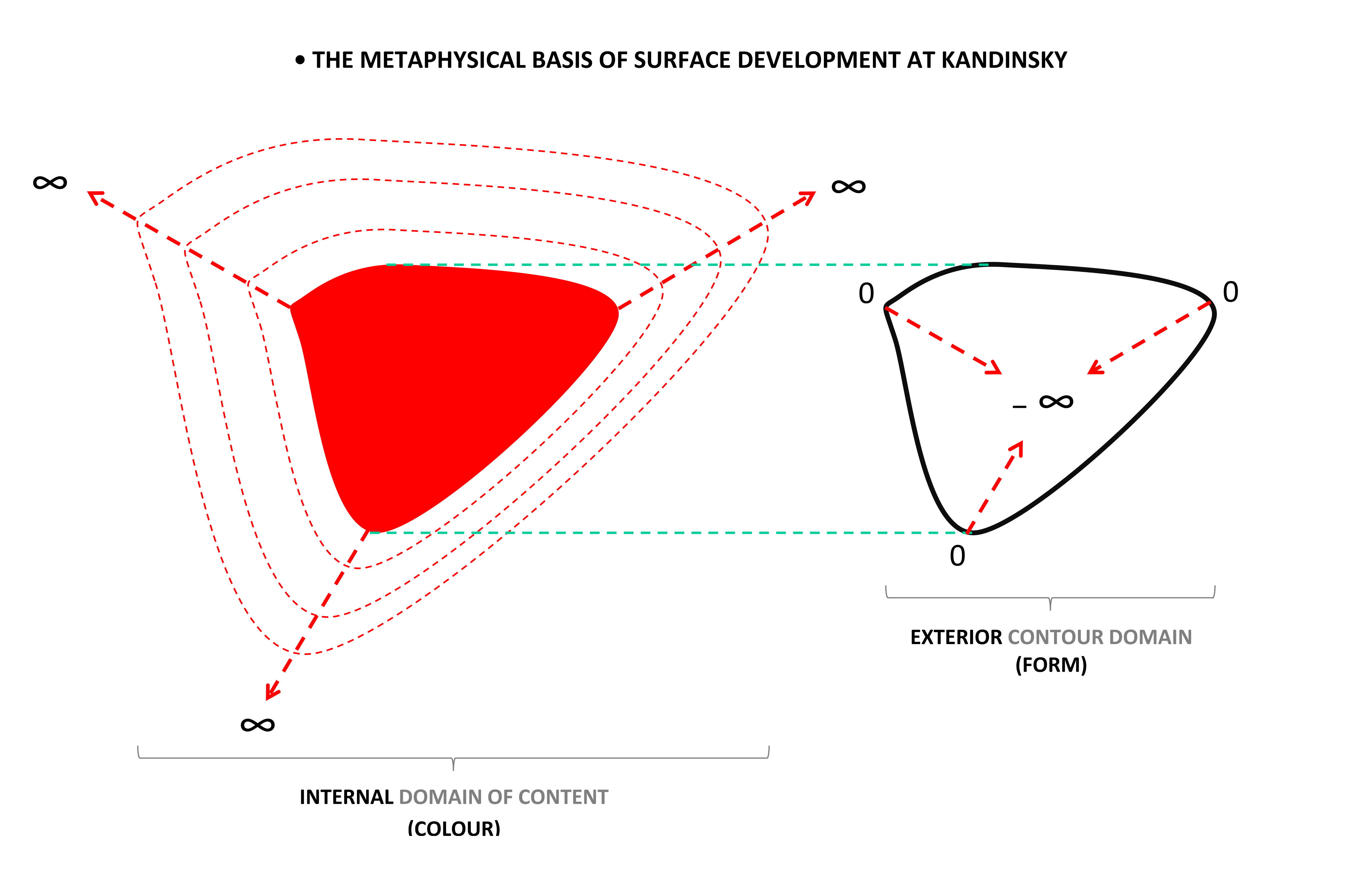

We have three main aspects of Kandinsky's structural theory: the metaphysical basis, the morphological-elemental structure, and the relationships they imply.

The METAPHYSICAL BASIS is the conceptual foundation of his theory. Through it, Kandinsky proposes a mental and emotional path for the artist that starts from the material and arrives at the spiritual aspects of the structural-lucrative manifestations – that is, from external observation to inner meditation (Kandinsky V. 1910-1911. p. 84-90). The aim of the spiritual route is the structural abstraction, concretized by "purely pictorial composition" (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 153). Abstraction consists of the artist's detachment from the academic-representational and naturalistic-structural resolution by simplifying surfaces with their constructive components and applying structural-autonomous and combinatorial relational models of correspondence between properties.

Kandinsky considers the notions of interiorization and spiritualization from an esoteric and religious point of view, but from a reductive and structural point of view, specific to SVAR, they resemble the neuronal-visual internalization based on bottom-up and top-down hierarchical processes. As for the notion of abstraction, it differentiates from the meaning of essentialization of SVAR, where abstraction is assigned to both representational and non-representational compositions, each with its own essentialised-attentional and visual purpose.

Kandinsky is presenting STRUCTURE in his theoretical works: "On the Spiritual in Art", which treats the notion of form, and "Point and Line in the Plane", which develops the concept of element.

The form is, from an external point of view, only the outline of surfaces with uniform chromatic content (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 165), and it manifests in its own right, as opposed to color, which cannot assert itself independently of the form-contour (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 162).

The modeling of form relates to the chromatic content of the surface, internally, by a functional convention, so that surfaces with rounded contours correspond to content with cool tones and surfaces with straight contours correspond to content with warm tones (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 163).

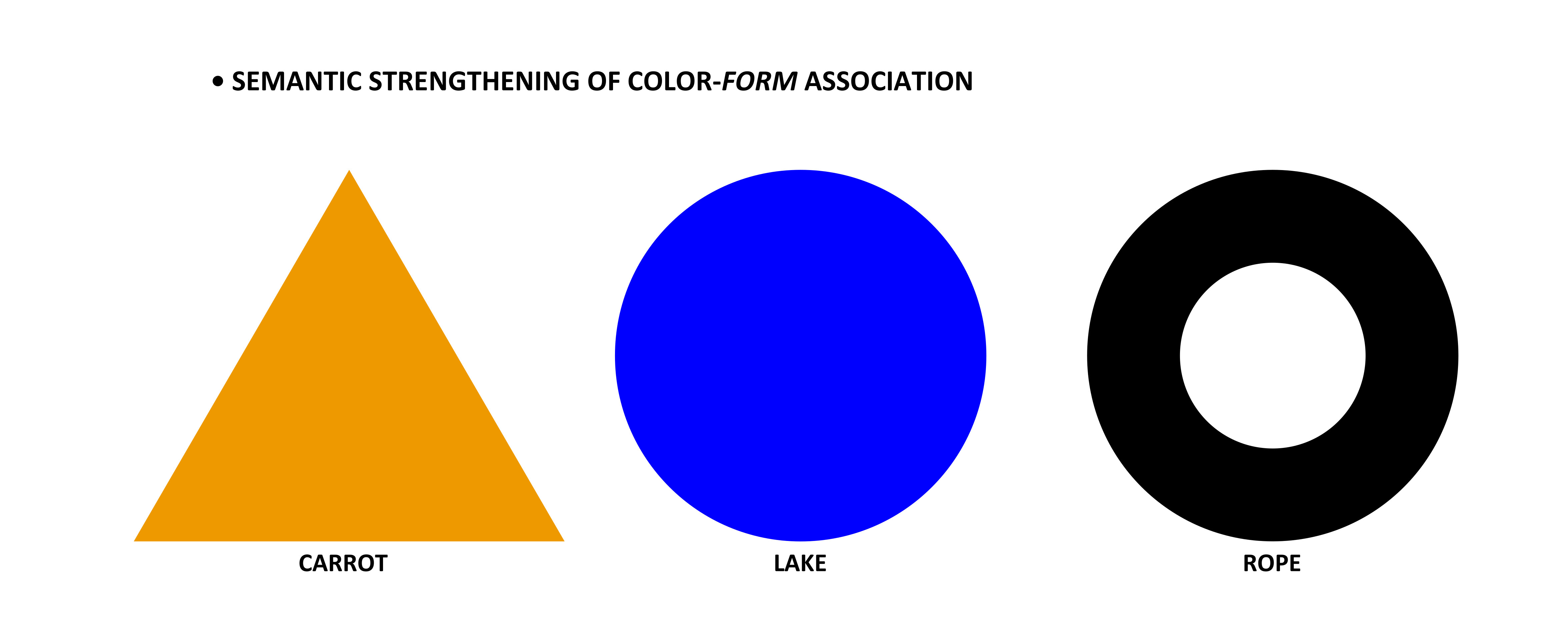

Kandinsky does not conceive form as an object-ground ensemble (see EXPO 1-METAPHISICS) but as a surface component of contour, distinct and autonomous from its chromatic content. Here, Kandinsky grasps from afar the Feature Integration Theory (Treisman, A., & Souther, J. 1986) in the need for pre-attentive subordination of chromatic content to the object delineated as form, where the two components merge through object recognition at the level of the V4 area (Roe A. W. & Chelazzi L. 2016). However, in Kandinsky's theory of correspondence convention between form and chromatic-spectral tones doesn't have an internal-neuronal basis.

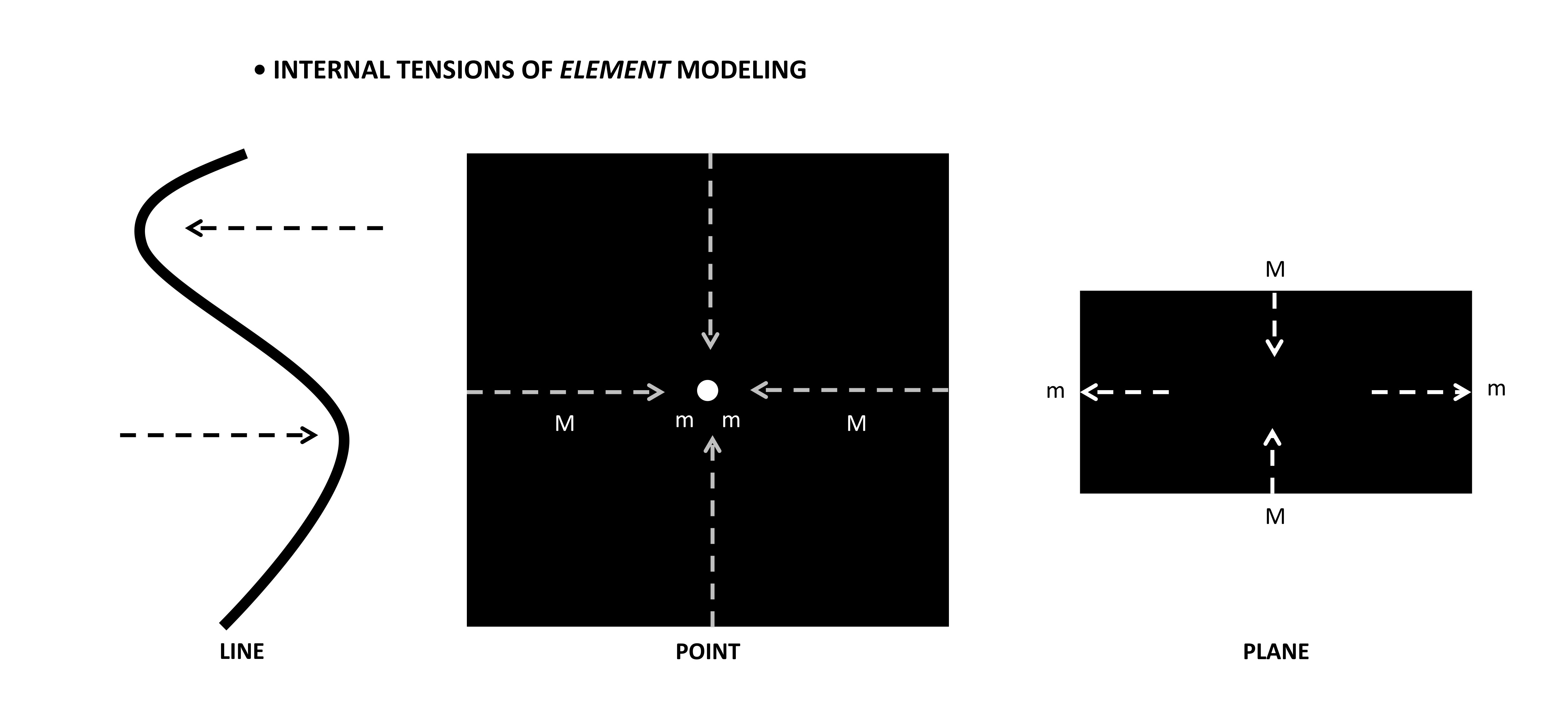

The elements help to develop the general theory of form and its geometric variations, which, in Kandinsky's conception, "have no description in mathematical terms" and are "equal citizens in the world of abstraction" (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 163). They are also defined as forms, that is, parts of open contour without content (point and line) or contour enclosing the content (of the plane) (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 29, 57, 115).

In the case of complex forms, Kandinsky disregards the analytic-mathematical possibilities of expressing line graphs as polynomial equations. Also, he does not intend to make a simple and basic classification of forms as concave and convex. Despite the mathematical character of the notion of element, Kandinsky does not approach it from the point of view of set theory and topology through belonging, inclusion, intersection, union, and other operations established between elements and sets (Devlin K. 1993, p. 1-6).

RELATIONSHIPS that define the elements include various spiritual perspectives: external (geometric, lucrative trace, perceived time and enumeration) (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 25, 28, 57, 115/p. 34, 98. ), and interior (the motor-lucrative tension generated by the shaping force of the working matter) (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 32-33, 57-58, 79).

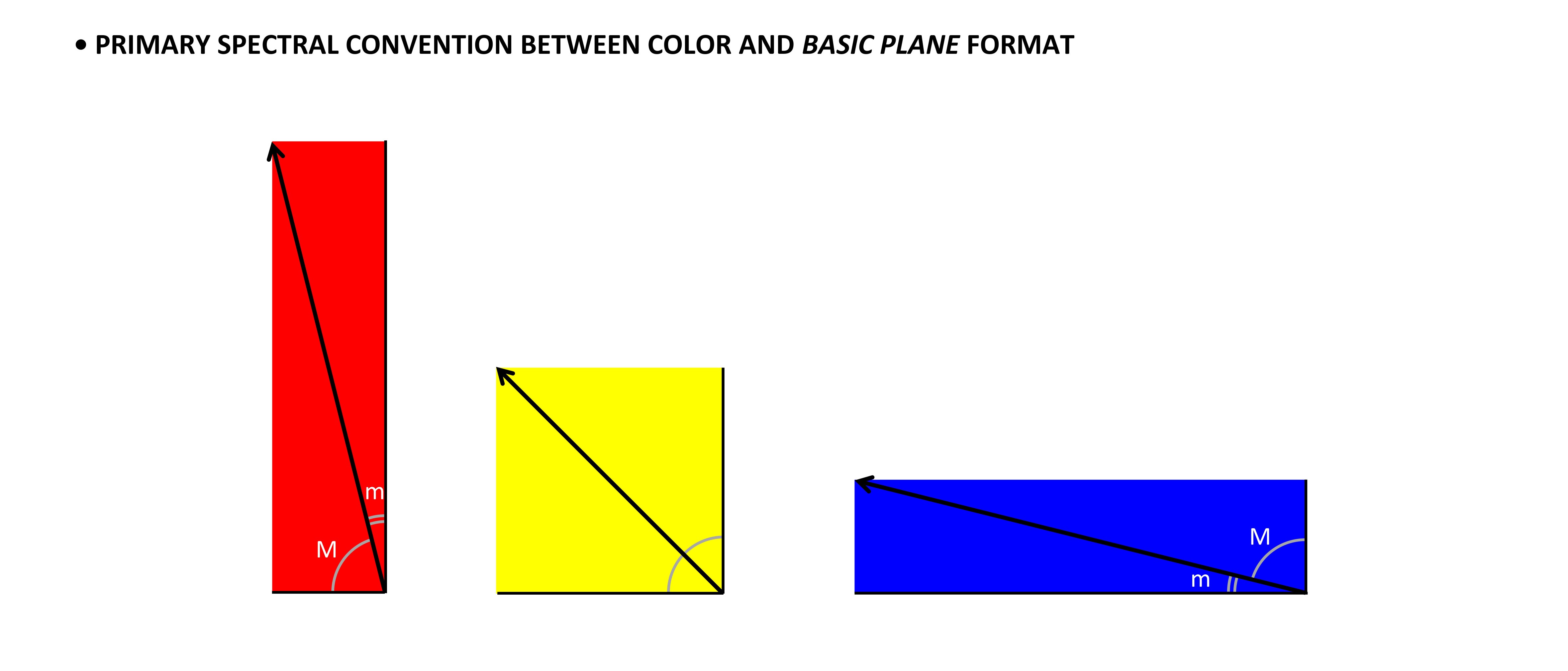

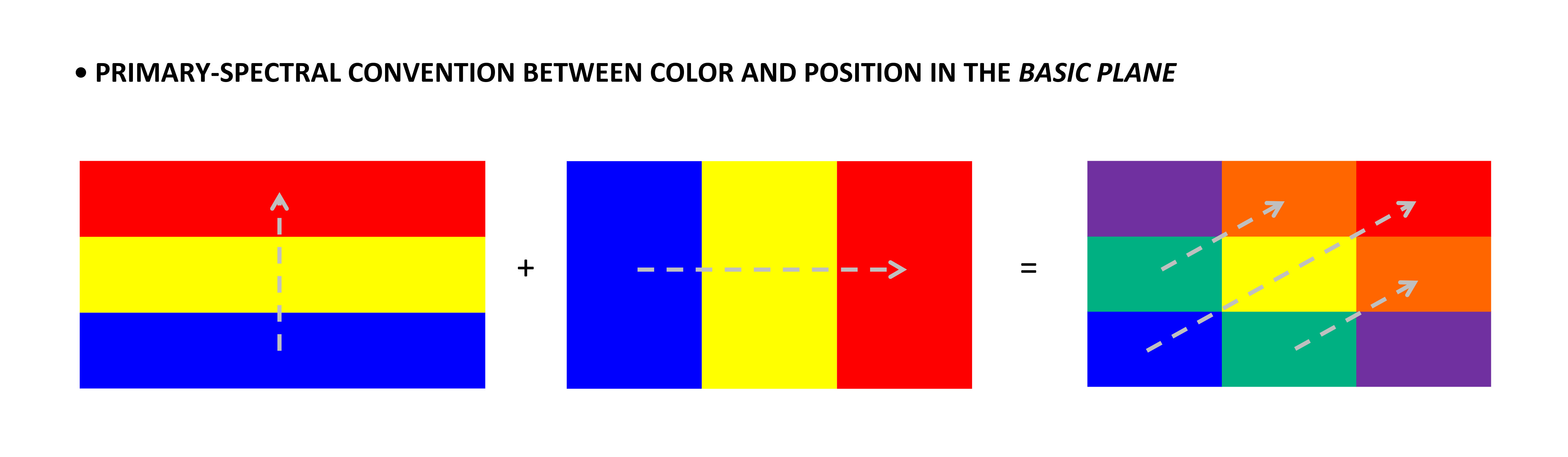

Kandinsky conceives the point in recessive-dominant opposition to the plane in which it includes it (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 29). Kandinsky describes the motor-lucrative tension that shapes the line as a system of vectors that mechanically model the element, which is constituted as a trace or memory of the motor forces that lucratively animate the working matter (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 57-58, 79-80, 84-89, 115-131). In the case of the plane, the tension manifests by the direction of the diagonal related to the orthogonal direction of entire plane (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 115-131). It consists of a system of chromatic tones distributed positionally by convention along the surface of basic plane.

Although he mentions the quantitative RELATIONSHIP between the size of the point and that of the basic plane, which contains it, Kandinsky neglects the visual finality of the quantitative relations between elements because he lacks the internalization argument supported by the role of the cortical area V5, necessary to ground the implicit movement and the property of sense for the attentional object (Kim C.-Y. & Blake R. 2007; Pavan A. et al. 2011; Zeki S. 2015, Krekelberg B. et al. 2005). It also lacks the internalization cues indicated in the primary cortex, V1, that ground the form attentively, based on collinearity (Chow H.M. et al. 2013 2015, 2016; Jingling L. 2013, 2017; Tseng C. & Jingling L. 2013, 2015; Zhaoping L. & Dayan P. 2006; Ng J. et al. 2007) and symmetry (Furmanski C. & Engel S. 2000; Li B. et al. 2002) between morphological components.

The compositional RELATIONSHIPS between elements unfold as a complex map of tensions and effector motor-lucrative forces, as inner manifestations (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 92) of juxtaposed forms, independent or distinct from each other (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 193) and combinatorically related (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 167).

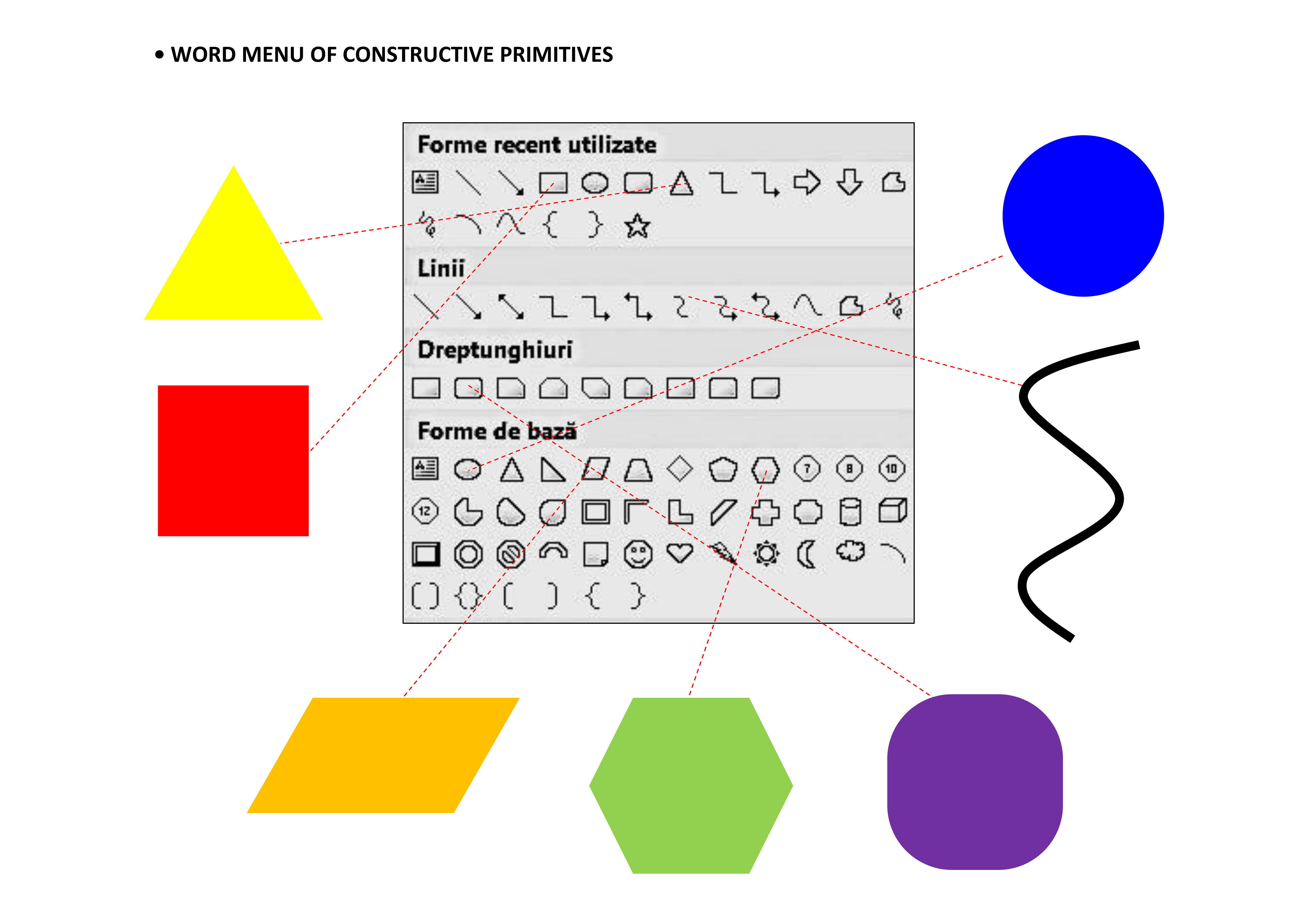

Kandinsky specifies that only juxtaposed and independent forms are essential to define the composition of an image by harmonical relations. The objective element, or center of interest, and the accents are incidental features. He sees the objective element and secondary accent relief as opposed to the uniformity of the background rhythm, achieved through discontinuity or chromatic-spectral dissonance. Forms resemble the objects chosen from a store or menu. The artist borrows them in order to put them on the basic plane of the working support (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 166).

Kandinsky does not approach the relationship between object and background visually. Perhaps the abandonment of the academic method of volumetric and representational beveling of planes also influenced his concept of attentional relationships in his abstract approach to composition. In his definitions of composition, Kandinsky gives greater importance to the notions of tension and lucrative shaping motor force but neglects their attentional-visual importance. When he relates composition to chromatic and linear harmony, he emphasizes the relationship between combinatorically composed forms and the conventional-positional context of the basic plane. In other words, for Kandinsky, compositional essentialization is not about determining the morphological object but about separating the surfaces with their chromatic content and determining the forces that led to their shaping as a trace, conserved as tension. Kandinsky has an atomistic or fragmentary conception of form, also supported by the notion of the menu, or storehouse, as the source of creative forms. Although it has no relevance in SVAR from an attentional point of view, today, the notion of a menu has a well-defined counterpart in graphic design through the tool menus, or primitives, used for editing and designing computer images.

Compositional balance comes from the decomposition of the more extensive elementary complexes into smaller and smaller subordinate ones. To achieve the decomposition, after the conquest of numerical expression and an exact theory of composition (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 93), would imply a considerable effort made by the theorist to separate and inventory the basic elements. Also, regarding numerical-elemental relationships, Kandinsky classifies compositions according to their complexity. The simple ones are melodic, and the complex ones are symphonic (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 215).

Kandinsky seems to grasp by the decomposition of elementary complexes and the subordination of elements the argument of selective attention, which we will develop at length in the method of deconstruction of surfaces and their morphological recurrence - even if he does not refer to a visual-attentional subordination, but to a motor-functional one, of color-form correspondence, related to the basic plane of the support. As for the effort of numbering, it corresponds in SVAR to the researcher's effort of detecting the colinearization and symmetrization paths of the morphological model by grouping surfaces and portions of surfaces after deconstruction.

Kandinsky considers the finality of the compositional relations between forms as an imagistic whole based on the relations between the inner and tensions and forces of the composed forms and elements (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 193).

By fixing the goal of compositional relations in achieving the imagistic whole, Kandinsky seems to tend towards the need for a relational understanding at the visual level. However, he cannot go beyond the horizon of the receptive and sensory-visual level, proper to the initial psychophysical period of the development of the science of visual perception. He does not develop a research instrumentary based on constructive maps of surfaces with their properties fixed synthetically. Such an approach would probably have had an all too obvious academic counterpart in studies of eclerage after material models. The autonomous and neural representation of space by cognitive maps processed and stored in the hippocampus was impossible when the theoretical work of Kandinsky was published. The first hypothetical mentions of cognitive maps appeared in behaviorist experiments in the middle of the last century. (Tolman E. C. 1948).

In Kandinsky's theory, time is also a compositional relationship. It is perceived differently from one element to another. In the case of the point, time refers to the motor-lucrative perception of the element, as Kandinsky associates the making of the point with the action of percussion in music and the animal world (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 34). In the case of the line, under the influence of the length notion, Kandinsky attributes to time a visual-ocular tracking function with different quantitative-comparative characteristics, perceived according to the type of the linear path and its direction (Kandinsky V. 1926, p. 98).

Kandinsky's notion of time is heterogeneous and confusing. He doesn't mention eye movements and possible associations with the focus times of visual attention by the different types of elements and assembled elements of composition Researchers in the field of visual attention and eye movement (eye tracking) had already developed tracking devices in the study of saccades in the 19th century (Wade N. J. 2010, p. 53), and in 1900, Raymond Dodge invented eye movement tracking by photography. In 1904, George Malcolm Stratton published studies of eye movements while watching graphic and aesthetically pleasing structures (Wade N. J. 2010, p. 57).

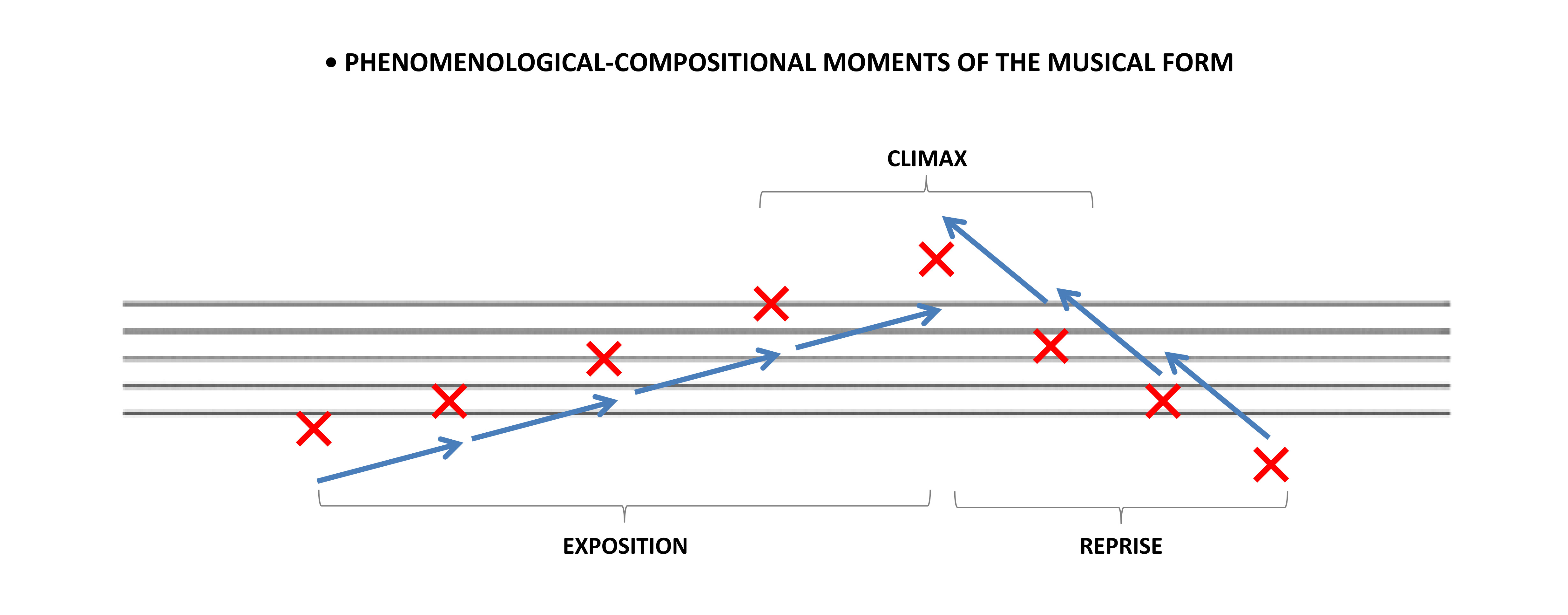

I don't intend to suggest by the critical approach that SVAR is opposed to the structural theory developed by Vassily Kandinsky. Yes, there are differences and principal oppositions, but I believe that SVAR will contribute through applied and pragmatic deepening to the structural understanding initiated at Bauhaus. Kandinsky's theory intentionally follows Arnold Schoenberg's musical compositional foundations (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 149, 206). The composer extended the use of dissonance by atonal combinatorics, leading to the assertion of atonalism, dodecaphony, and serialism currents in the musical composition (Shannon A. M. 2008). SVAR follows the reductive-phenomenological principles consistent with the structure of classic musical forms found in the pedagogical speech of Sergiu Celibidache (Schmidt-Garre J. 1992, fr. 52:13-53:58/57:03-59:10/1:01:51-1:02:37), but also in the Spanish school of musicology (Roca J. A.G. 2017) and the phenomenological conception of conductor and composer Ernest Ansermet (Ansermet E. 1987).

For them, the musical form cannot rely on tonal combinations and permutations but on a sound-attentive hierarchy of tonal intervals consisting of three composition moments: the exposition, the climax, and the resolution, with their characteristics of consonant-dissonant tonal alteration and rhythmic alternation of the accents. From this point of view, permutational or combinatorial processes remain simple sound constructions without musical and cognitive relevance (Ball Ph. 2011).

I accept these fundamental differences not as an abyss or as an irreconcilable separation between the two directions of visual-artistic structural conceptualization but from the point of view of a complementarity and conceptual continuity of the effort of knowledge. The abstractionist direction of Kandinsky does not deny representational art (Kandinsky V. 1921, p. 165) but extends the possibilities of visual structuring beyond the limits of volumetry and eclerage. It probes the attentive limits of constructing by the harmony and combination between surfaces, conceived as modeled traces related to the basic plane of the support. Thus, there comes the need for conceptual counteraction and balancing by SVAR through the authentic awareness of the opportunities of structural synthesis and abstraction, taking place both within the representational compositions and non-representational ones.

So, Kandinsky's abstractionism is only the ”prelude” of abstraction. The artist is concerned with the structure of the surfaces that make the morphological background. He relies on combinatorial, analytical, intuitive, and speculative relations, which ensure their constructive harmony. By difference, SVAR aims to deepen the visual object from a morphological-attentive point of view through a reductive, synthetic, and essentializing approach – that is abstract in itself. Abstractionism is concerned with the isolation of the compositional context, with its lucrative constructive components, understood mechanistically way, while SVAR achieves abstraction through visually understanding the influence of background context over the morphological object of attention.

RESOURCES:

Ansermet E. 1987. – Les fondements de la musique dans la conscience humaine vol I, II. Langages. À La Baconnière, Neuchâtel. Corbaz S.A., Montreux.

Ball Ph. 2011. – Schoenberg, serialism and cognition: Whose fault if No one listens? Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, Vol. 36, No. 1.

Berggruen O. (curat.) 2013. – Paul Klee-The Bauhaus Years, Works from 1918–1931. On the ocasion of exposition: Paul Klee—The Bauhaus Years: Works from 1918–1931, 2 Mai – 14 June, 2013. Dickinson, New York.

Chow H.M., Jingling L. & Tseng C. 2013. – Collinear integration affects visual search at V1. Journal of Vision 13(10):24: 1–20.

Chow H.M.& Jingling L. 2015. – A Salient and Task-Irrelevant Collinear Structure Hurts Visual Search. PLoS ONE 10(4): e0124190. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124190.

Chow H.M., Jingling L. & Tseng C. 2016. – Eye of origin guides attention away: An ocular singleton column impairs visual search like a collinear column. Journal of Vision 16(1):12: 1–17.

Devlin K. 1993. – The Joy of Sets: Fundamentals of Contemporary Set Theory. Springer Science&Business Media, New York.

Furmanski C. & Engel S. 2000. – An oblique effect in human primary visual cortex. Nature Neuro-science / volume 3, no 6 / june.

Gropius W. 1919. – Baukunst im freien Volksstaat, în Deutscher Revolutions Almanach fur das Jahr 1919: Arbeiter die Ereignisse des Jahres 1918. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg.

Gropius W. 1923. – The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus, în Bayer H., Gropius W. & Gropius I. (ed.). Bauhaus 1919-1928: Exhibition Catalogue. Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1938.

Hasan Y. 1999. – Paul Klee si pictura moderna: Studiu despre textele lui teoretice. Editura Meridiane, București.

Isaacs R.R. 1991. – Gropius : An Illustrated Biography of the Creator of the Bauhaus. Boston : Little, Brown.

Itten J. 1974. – The Art of Color: The Subjective Experience and Objective Rationale of Color. Wiley, New York.

Itten J. 1921. – Analysen Alter Meister in Bruno Adler (ed): Utopia: Dokumente der Wirklichkeit, I/II, Weimar.

Itten J. 1930. – Tagebuch 1930: Beiträge zu einem Kontrapunkt der Bildenden Kunst. C. Wagner (ed.).

Schnell & Steiner 2024. Itten J. 1963. – Design and Form: the Basic Course at the Bauhaus. Reinhold Pub. Co., New York.

Itten J. 1974. – The Art of Color: The Subjective Experience and Objective Rationale of Color. Wiley, New York.

Jingling L. 2013. – The configuration effect in visual search. Article in Journal of Vision · July.

Jingling, L., Lu Y.H., Cheng, M. & Tseng C. 2017. – Collinear masking effect in visual search is independent of perceptual salience. Atten Percept Psychophys 79, 1366–1383.

Kandinsky V. 1910-1911. – Content and Form (Odessa), în Complete Writings on Art, Volume One (1901-1921). Lindsay K. C. and Vergo P. (ed.). The Documents of Twentieth Century Art. Motherwell R. & Flam J.D. (ed.). G. K. Hall & Co. Boston, Mass 1982.

Kandinsky V. 1921. – On the Spiritual in Art, and Painting in Particular, With Eight Plates and Ten Original Woodcuts (second edition). R. Pipe & Go, Munchen, în Complete Writings on Art, Volume One (1901-1921). Lindsay K. C. and Vergo P. (ed.). The Documents of Twentieth Century Art. Motherwell R. & Flam J.D. (ed.). G. K. Hall & Co. Boston, Mass 1982.

Kandinsky V. 1926. – Point and Line To Plane: Contribution to The Analysis of the Pictorial Elements. Rebay H. (ed. & pref.). Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Museum of Non-Objective Painting, New York 1947. Cranbrook Press Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

Kim C.-Y. & Blake R. 2007. – Brain activity accompanying perception of implied motion in abstract paintings. Spatial Vision, Vol. 20, No. 6: pp. 545–560.

Klee P. 1961. – Notebooks, Volume 1: The Thinking eye. Jurg Spiller Percy (ed.). Lund, Humphries & Co., Ltd, London.

Krekelberg B., Vatakis A. & Kourtzi Z. 2005. – Implied Motion from Form in the Human Visual Cortex. PresS. J Neurophysiol (August 17).

Li B., Peterson M. R. & Freeman R. D. 2002. – Oblique Effect: A Neural Basis in the Visual Cortex. Journal of Neurophysiol, Vol. 90, July: 204 –217.

MacCarthy F. 2019. – Gropius: The Man Who Built the Bauhaus. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ng J. et al. 2007. – A Survey of Architecture and Function of the Primary Visual Cortex (V1). Hindawi Publishing Corporation, EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, Article ID 97961.

Pavan A., Cuturi L. F., Maniglia M., Casco C., Campana G. 2011. – Implied motion from static photographs influences the perceived position of stationary objects. Vision Research 51: 187–194.

Plato 1965 – Timaeus. Translation and Introduction F. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, Aldine Press & Letchworth, Bedford Street – London, Great Britain, II: 9-12. First published in Everyman’s Library 1965.

Roca J. A.G. 2017. – Fenomenología de la música de Sergiu Celibidache y su influencia en la dirección de orquesta en España (TESIS DOCTORAL). Departamento de Ciencias Humanas Universidad de La Rioja.

Roe A. W., Chelazzi L., Connor C. E., Conway B.R., Fujita I., Gallant J. L., Lu H. & Vanduffel W. 2012. – Toward a Unified Theory of Visual Area V4. Elsevier Inc., Neuron Review 74: 12-29.

Schmidt-Garre J. (reg.) 1992. – Celibidache: You Don't Do Anything, You Let It Evolve (DVD doc.). Studio Arthaus. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOz6LlFbPHk.

Shannon A. M. 2008. – Kandinsky’s Dissonance and a Schoenbergian View of Composition VI. USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/122.

Thurlemann F.1982. – Paul Klee: Analyse Sémiotique de Trois Peintures.L’Age d’Homme.

Tolman E. C. 1948. – Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psychological Review, July, vol. 55, no. 189-208.

Treisman, A., & Souther, J. 1986. – Illusory words: The roles of attention and of top–down constraints in conjoining letters to form words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 12(1), 3–17.

Tseng C.& Jingling L. 2013. – Collinearity Impairs Local Element Visual Search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. doi: 10.1037/a0027325.

Tseng C.& Jingling L. 2015. – A Salient and Task-Irrelevant Collinear Structure Hurts Visual Search. PLoS ONE 10(4): e0124190.

Wade N. J. 2010. – Pioneers of eye movement research. i-Perception, volume 1, pages 33 – 68.

Zeki S. 2015. – Area V5—a microcosm of the visual. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, April, Volume 9, Article 21.

Zhaoping L. & Dayan P. 2006. – Pre-Attentive Visual Selection. Neural Networks, Volumn 19, Number 9, Nov.: 1437-1439.

SOURCES OF EDITED IMAGES:

HENRY VAN DE VELDE

https://casabellaweb.eu/2017/04/02/henry-van-de-velde/

WALTER GROPIUS

GRAND-DUCAL SAXON ART SCHOOL – WEIMAR

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/veld006gesc01_01/veld006gesc01ill85.gif

BAUHAUS IN WEIMAR

https://www.diatomea.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/de7c50f41025a5ed53987e7e96571bb4-1024x816.jpg

BAUHAUS IN DESSAU

LYONEL FEININGER: CATHEDRAL – 1919

HERBERT BAYER: ANNIVERSARY POSTER OF 50 YERS –1968

https://a.1stdibscdn.com/archivesE/upload/1722654/f_3083302/IMG_8722_org_z.jpg

WALTER GROPIUS: CURRICULUM DIAGRAM – 1923

https://th.bing.com/th/id/OIP.fVM_fcmN6HmRqm1djw1GdwAAAA?rs=1&pid=ImgDetMain

JOHANNES ITTEN

https://th.bing.com/th/id/OIP.SwlaZMAEqPNxnCjTh3g4fgHaJ6?rs=1&pid=ImgDetMain

PAUL KLEE

https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2022/12/GettyImages-171161933.jpg

VASSILY KANDINSKY

STUDENTS IN ONE OF JOHANNES ITTEN’S “UNLEARNING” EXERCISES AT THE BAUHAUS – WEIMAR

https://arthistoryteachingresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Itten-Bauhaus-Class-768x580.jpg

IN THE RHYTHM

https://www.kunstkopie.de/kunst/paul_klee_11025/rhytmisches.jpg

NEW HARMONY

https://img.kingandmcgaw.com/imagecache/1/3/si-134723.jpg_maxdim-1000_resize-yes.jpg

STATIC-DYNAMIC GRADATION

https://ro.pinterest.com/pin/405324035184849282/

COMPOSION VII

SEMANTIC STRENGTHENING OF COLOR-FORM ASSOCIATION

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feature_integration_theory#/media/File:Treismanshapes.png

ARNOLD SCHÖENBERG

https://www.jaytomlin.com/newjaytomlin.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ArnoldSchoenberg-1200x940.jpg

SERGIU CELIBIDACHE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOz6LlFbPHk

ERNEST ANSERMET

https://notrehistoire.ch/entries/J78rgEbDWEl